Why Fiscal Dominance Is Rewriting the Rules of Finance

For nearly half a century, the Federal Reserve was the undisputed puppeteer of economic cycles.

A raise here, a cut there — and Wall Street, banks, and Main Street danced accordingly.

But something has broken.

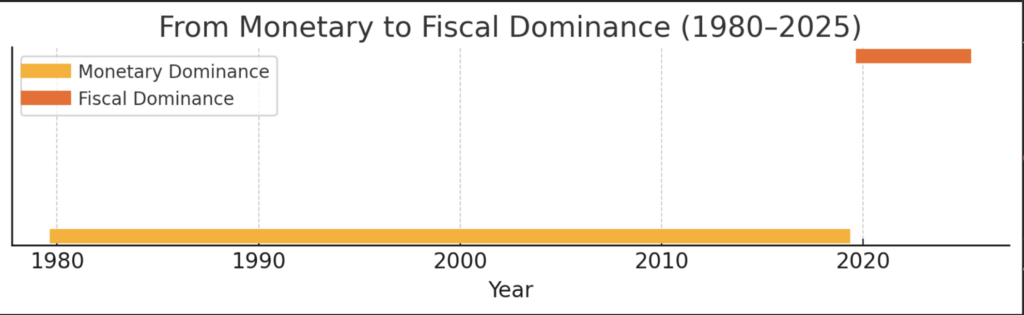

The U.S. has quietly crossed into a new era: fiscal dominance — where government deficits, not interest rates, now steer the economy’s course.

This seismic shift is being overlooked by most investors, economists, and policymakers. Yet its consequences could define markets, inflation, and asset returns for decades.

If monetary policy was the “invisible hand” of the past, fiscal firehoses are the new hands on the wheel.

The Shift: From Bank Lending to Government Spending

In the post-Volcker world (1980s onward), the Fed ruled because private credit ruled.

Money creation was primarily a function of commercial bank lending.

Higher rates = fewer loans = less money.

Lower rates = more loans = more money.

Simple. Predictable. Powerful.

But today:

-

Annual U.S. fiscal deficits ($2T–$3T) regularly exceed net new private loan creation.

-

Government is injecting more new dollars into the system than banks are.

In short: monetary policy adjusts the speed limit, but fiscal policy controls the size of the highway.

| Era | Dominant Money Creation | Policy Lever | Primary Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980–2010 | Bank lending | Fed rates | Private sector credit |

| 2020 onward | Government deficits | Fiscal policy | Sovereign spending |

Why Interest Rate Hikes Matter Less

Yes, rate changes still influence mortgage rates, business borrowing, and risk appetite.

But unlike households or small businesses, the U.S. government does not “borrow less” because rates go up.

In fact, higher rates increase deficits through higher debt service costs — forcing more issuance.

Higher Fed Funds Rate = Higher Treasury Deficits = More Treasury Supply

This is the fiscal flywheel.

And it’s one the Fed has little power to stop without causing major liquidity shocks.

Liquidity Floors: Why QT Will Likely End by 2025

Quantitative Tightening (QT) — the Fed’s strategy of shrinking its balance sheet — faces an invisible limit:

the liquidity floor of the banking system.

Once banks feel starved for reserves, money market dysfunction begins.

That’s exactly what happened in late 2019, forcing the Fed to stealthily restart QE months before COVID-19 appeared.

Base Case Forecast:

-

QT ends by late 2025 (at the latest)

-

Possible balance sheet expansion begins even with inflation still above 2%

This will shatter the post-2008 narrative that QE was strictly a crisis tool.

In a fiscally dominant world, balance sheet expansion becomes structural, not exceptional.

Tariffs and Fiscal Shocks: Bigger Than 100 Basis Points

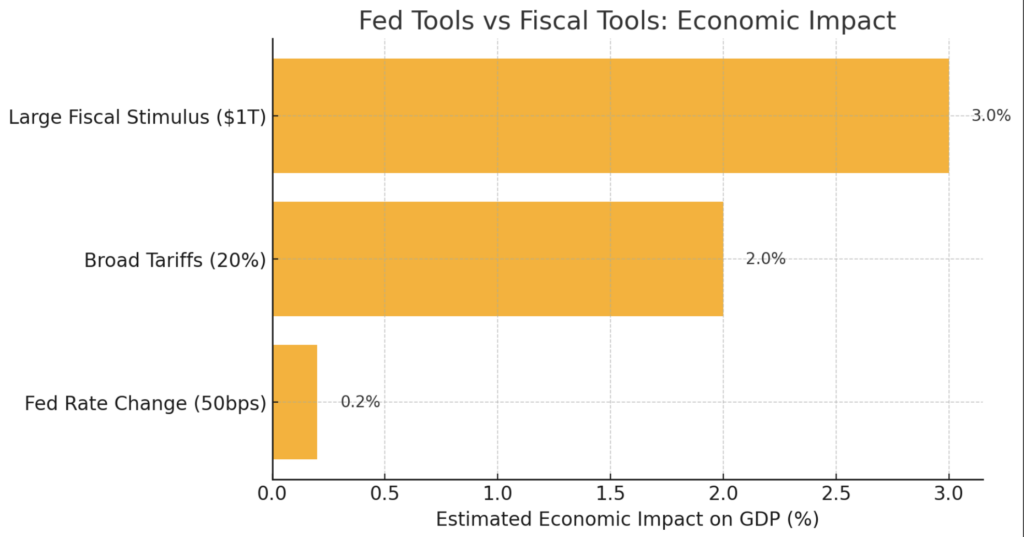

Most mainstream commentary obsesses over whether the Fed will hike or cut by 0.25% or 0.50%.

In reality, fiscal shocks dwarf monetary nudges:

Example:

If tomorrow the U.S. imposed 20% tariffs across all imports:

-

Prices would spike

-

Global supply chains would realign

-

Growth patterns would shift

-

Inflation could surge more than any Fed move would counteract

| Event | Estimated Economic Impact | Equivalent Fed Action |

|---|---|---|

| 50bps Fed hike/cut | 0.1%–0.3% GDP adjustment | Minor |

| 20% across-the-board tariffs | 1%–3% GDP shift | Major |

| $1T new fiscal stimulus | 2%–4% GDP boost | Major |

Fiscal Dominance: Investment Implications

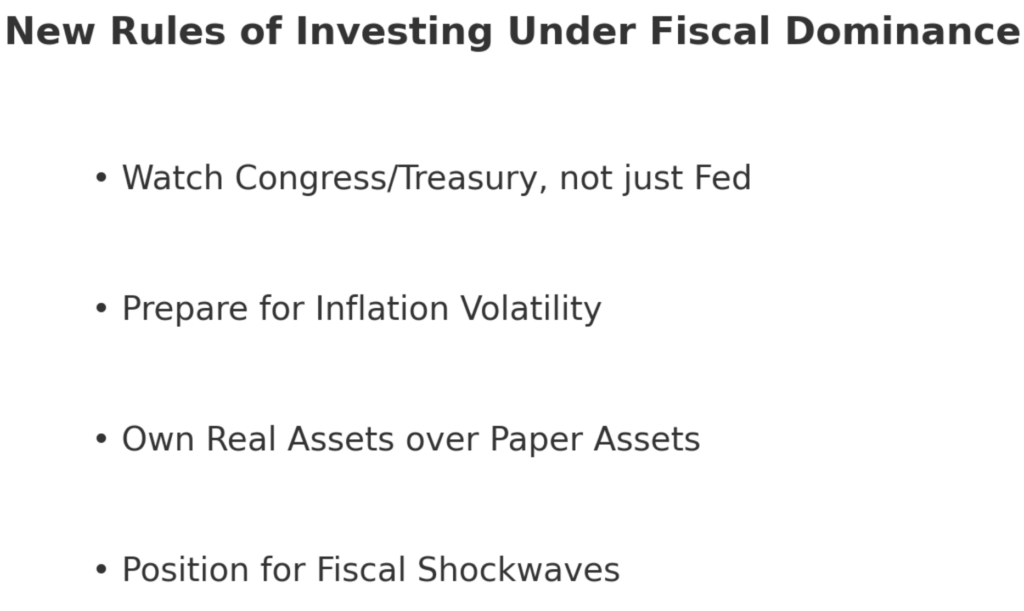

If the Fed is now a marginal player, investors must rebuild their frameworks.

New Rules of the Game:

-

Real assets (infrastructure, commodities, energy) will outperform paper assets.

-

Hard money hedges (Bitcoin, gold) gain over fiat-based assets.

-

Bond investors must demand a growing fiscal risk premium.

-

Quality equities (pricing power, real asset ownership) become more valuable.

Key Tactical Shifts:

-

Watch Congress and Treasury, not just Fed minutes.

-

Focus on policy-induced price shocks (tariffs, subsidies, tax changes).

-

Prepare for higher inflation volatility, even if nominal rates remain “stable”.

The Invisible Hand Has Changed

The illusion that 12 unelected officials in Washington can fine-tune the $27 trillion U.S. economy with minor rate tweaks is fading fast.

We are entering a messier, less predictable era — where fiscal impulses, geopolitical shifts, and global fragmentationdrive outcomes more than sterile monetary models.

The new invisible hand is Congressional spending, structural deficits, and national industrial policies.

The sooner investors recognize the new playbook, the sooner they can position not just to survive — but to thrive.